Ten Versions of Kafka

(Dix Versions de Kafka)

by Maïa Hruska

Kafka and Jorge Luis Borges:

two men in a maze

Within just one lifetime, the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges managed to devote to Franz Kafka more than eighteen translations and at least fifty prefaces, prologues, articles and lectures. Kafka appears to have been so profoundly a part of his life that Borges had difficulty pinpointing the moment he first encountered him as a reader. He sometimes said it was during his student years in Geneva, where he studied German literature, between 1914 and 1918; at other times he dated it to 1925, the year when the Revista de Occidente, of which he was an avid reader, printed a first, anonymous translation into Spanish of The Metamorphosis.

The Revista, a cultural magazine published in Paris by the philosopher José Ortega Y Gasset, was to the Hispanic world what the NRF (Nouvelle Revue Française) was in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, or indeed the journal Innostranaya Literatura in Moscow: a barometer for the literary scene, revealing which writers were on the rise. It would be fair to say that the Buenos Aires of the 1920s was to Madrid what Prague had been to German literature a few years earlier: both a hive of activity and a provincial outpost. Kafka, who spent his entire life in this composite capital where Jewish, German, Czech, and, from 1917 onwards, Russian communities rubbed shoulders, never felt like he belonged to any of them. Despite his Anglo-Castilian heritage and his Germano-Latin education, Borges, too, kept himself at one remove from all the categories to which he belonged and of which he was constituted.

Borges and Kafka had further common ground in that they shared the same regret: that of not being sufficiently Jewish. Kafka came from a family of assimilated Ashkenazi Jews. He hated the fact that he had not received a religious education that might have given him some semblance of a tradition, or roots, to cling to. This was the central theme of his work Letter to His Father (1919). Similarly, Borges, fascinated as he was by the Kabbalah, to which he dedicated several short stories, including The Aleph, regretted not belonging to the only people to have chosen the book (with a small ‘b’ or a big one) as their home. In 1934, Borges responded to a claim made in the nationalist Argentine newspaper Crisol, which suspected him of being “secretly Jewish”, by penning a profound and amusing article entitled: “Me, a Jew” (Yo, Judio). In it, he declared that he had sought in vain for any trace of a Jewish ancestor, by researching his genealogy over several centuries. Had he found one, he would have proudly shouted his Jewishness from the rooftops.

One need only read Santiago Amigorena’s magnificent novel, The Ghetto Within, to understand what kind of city Buenos Aires was from the late 19th century onwards. The tidal waves of immigrants – Italian, Spanish, French, Russian, Jewish – had transformed it into a European capital in exile. There, in its hothouse atmosphere, Borges observed the different cultures, languages, religions and imaginations crossing paths with one another, merging and becoming synthesised, often incompletely and sometimes unhappily. In both his work and Kafka’s, these multiple intersections were to become an obsessive, omnipresent image.

The thread that connects Kafka’s maze to that of Borges is nonetheless tangled, and even broken, in more than one place.

Borges was a translator before he was a writer. By toiling like a workhorse on his translations he had brought the modernity of Poe, Woolf, Faulkner and Joyce to Argentina. He did not start translating Kafka until 1938.

During a conversation with an American student in 1976, Borges stated that he had procured the complete works of Kafka from the bookshop of the Goethe Institute in Buenos Aires. Kafka’s works had been banned in 1933, though, and had even been gleefully burned by the Nazis. Had someone neglected to inform the German bookseller that Kafka was an enemy of the Volk, the Geist, the Blut? It was not beyond the bounds of possibility, of course, that the orders from the Reichstag had taken some time to make their way across the Atlantic. Kafka himself seemed to have foreseen just such a scenario in a short story published twenty years earlier, in 1919, in the review Selbstwehr. In An Imperial Message, a courier charged with passing on an emperor’s missive gets lost in the interminable corridors of the palace. The layout of the private rooms is so serpentine and twisted that the messenger gets tied up in knots trying to find a way through. The intended recipient, “sitting at the window” as if in an Edward Hopper painting, can only wait, and wait some more, endlessly speculating about the contents of a letter that will never reach him. This story is The Castle inverted: whereas the surveyor named K desperately tries to find the way in, the messenger wears himself to death trying to find the way out.

An Imperial Message depicts the two boa constrictors wrapped around modern man: on top, subordination to orders; and below, the impossibility of apprehending the infinite. Like most of Kafka’s short stories, it contains no more than twenty lines. In one fell swoop, it ticked off the two qualities that Borges admired in a work: “being short and infinite”. This story may be just a miniscule fragment of Kafka’s oeuvre, but it nonetheless reproduces it and reflects it in full. The content of the imperial missive is never revealed to the recipient, but that is not due to any tragic incident (the messenger is not struck down by lightning, or killed by an assassin’s bullet), or to a lack of will (the messenger is by no means lazy). Rather, it is because the courier must wander helplessly in a world for which he was never given the manual. What we are talking about here is the physiology of Kafka’s world, in the sense given to this word by Flaubert when he talked of his characters’ ‘physiology’ as a way of explaining their fate. The story An Imperial Message has the entire Kafka genome within it: it contains both The Castle and The Trial. The expectation of a revelation that never comes. Every short story by Kafka is similar to the others, yet unique. Their respective motifs reverberate infinitely inside one another.

Kafka chez les Soviets

For the Soviets, the whole drama around Kafka, as we have said, was his sobriety. Contrary to a suggestion made by the literary review Action, Kafka was not a sombre writer, but a sober one, irredeemably sober: nothing could intoxicate him. Not the revolution, not women, not ideals. Born in the same cradle as the diverse trends that governed the world of his day – National Socialism, Communism, Zionism, Freudianism – he remained utterly indifferent to them. The romantic fascination shown by his contemporaries for the great sweep of history – the history that Georges Perec saw as wielding a “great axe” – seemed distant to him, not to say ridiculous. That kind of history was supposed to just keep bubbling away in the background. The only axe to which Kafka paid any attention was the one that “shattered the frozen sea within us”, namely, literature. And Bolshevik Revolutions are not brought about with tools like that.

Let us take for instance his elegant diary entry for 3rd August 1914: “Russia declares war on Germany. Afternoon: swimming pool.” Kafka knew that words held little sway over the world. So he might as well go on tracing his lines and his lengths, with the swimmer’s shortness of breath, from one end of his notebook to the other, his gaze fixed on the tiled floor of the pool. He kept up a sustained correspondence with his sister Ottla throughout the four years of the war. Even though Ottla’s husband had enlisted to fight on the Russian front, none of Kafka’s letters or albums made the slightest allusion to the bloodshed or to the revolution of 1917. He evaded the great calls to arms of his day. Real life was happening somewhere else. It was the same after the war: there was no shouting for joy, no cry of horror.

From 1918 onwards, the world around Kafka reconfigured itself one treaty at a time, as is customary in that part of Europe, where pieces of scrap paper determine whether nations and their men live or die: the Treaties of Trianon, Versailles, Saint-Germain, Brest-Litovsk; the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The Habsburg monarchy was being dismembered. The first Czechoslovak Republic was emerging. The face of the countries around it changed: Austria, Germany, Russia and Poland all became unrecognisable. Overnight, the continent lost the bureaucratic apparatus at its centre, the one that, for several centuries, had seen to it that fifteen different nationalities could coexist. The administrative, legal, social, and political systems that Kafka had known collapsed. The first apparatchiks appeared, and the first stateless persons too. The latter were the ultimate foreigners, invisible, undefined. Pariahs with no papers, whom the authorities looked on in the same way that religious communities looked on illegitimate children. Hannah Arendt would have labelled them as cosmopolitan. Individuals “with a passport for every state but their own”. In a word, men like Joseph K.

Was Kafka so perceptive a prophet that the world around him set about imitating what he had imagined? It was rather that he was a shrewd observer: the distance he built up between himself and the world had made him sensitive to details no-one else seemed to have noticed. Kafka did not need to read the papers: living under the same roof as his parents was enough to make him understand the inner workings of self-flagellation and arbitrariness. As a lawyer specialising in insurance and the holder of no fewer than three citizenships in twenty years, Kafka had also had the opportunity to spend time around public administrations, offices and factories. He had seen how the mechanism of bureaucracy enabled an empire or an employer – even one that was running out of puff – to fuel itself.

In 1906, the German sociologist Alfred Weber, brother of Max Weber, chaired the jury that awarded Kafka his doctorate in law at Prague University. The Weber brothers were shaping a new discipline at that time: the sociology of organizations. This subject involved studying bureaucracy from the inside, i.e. from the point of view of its functionaries. Kafka’s characters were sociologists too, in a way. They studied this same bureaucracy, but from the bottom – and therefore from without. K. would never penetrate to the heart of the bureaucratic reactor in The Castle. That was the conclusion at which the novel arrived. So much the better, the Weber brothers might have said in response! The laws that banned Jews from becoming civil servants would be their salvation, or so they believed. In this way, they would avoid being subjugated by the machine. Their prediction proved overly optimistic, of course, but perhaps it explained, if only in some small way, how Kafka escaped all indoctrination.

Zionism, Anarchism, Communism, psychoanalysis, science, Hasidic Judaism: none of them earned any lasting commitment from Kafka. A diary entry from 23rd January 1922 reads: “For my part, not a single rule for living has proved its worth, not in the slightest.”

Kafka was not receptive to any great leaps forward. The only leap that interested him was the one “outside the ranks of murderers”, in other words: the craft of writing. He used to repeat it over and over, in puerile fashion perhaps, to his fiancées, his parents, his friends, his boss, his diary: “Literature is all I am, and I neither want, nor am I able, to be anything else”; “my situation is unbearable to me because it contradicts my sole desire and my sole vocation, namely literature”; “I hate everything that is not related to literature.” This was the only point on which he was somewhat limited. Writing was his only limitation, the only thing delineating the space he occupied, his only source of quietude. He restricted this space still further because his entourage used to invade it with no warning. When his fiancée Felice asked him why he didn’t want to live with her, he replied: “One is never sufficiently alone when one writes, there is never enough silence around one and the night is less like the night than normal, too.” He begged her to understand that a life with true sovereignty is necessarily lived underground. He asserted his right to withdraw to a basement, an attic, a bedroom, anywhere, just so long as he could find peace there.

Milan Kundera wrote that a novelist does a demolition job on the house, then uses the bricks to build a different one: that of their novel. Montaigne wrote of “the room at the back of the shop that is entirely ours, entirely free, where we establish our true freedom and find our primary retreat and solitude.” Kafka, for his part, reclaimed the inhabitable space that went with that back room, along with the right to withdraw to it whenever he saw fit.

In Czech, as in all the Slavic languages, the word pokoj has multiple meanings, a fact that certainly would have been known to Kafka and that might have delighted Virginia Woolf. Pokoj denotes ‘room’ and ‘a room’, but also a form of tranquillity, of quietude, of (psychological) peace. Pokoj exists in a topographical sense as much as it does as a utopian ideal. Dej mi pokoj: this is how you ask to be left in peace, but it is also how you ask to be given digs, a space just for you. If given a literary definition, pokoj could be said to mean the cell that forms the elemental basis of the self. The physical place where you write and, if circumstances dictate, the psychological space that you take with you, in order to redeploy it elsewhere. Pokoj is the capturing of something precious and precarious: the ability to be certain no-one is going to disturb you.

Kafka and Alexandre Vialatte: make me laugh

Vialatte told the story of his first encounter with Kafka many times. A century on, it has lost none of its mystery. At the age of twenty-five, while he was spending the winter of 1925 in Mayence, Vialatte had an anonymous parcel handed to him. “There was snow falling. The courier opened the door. He looked like a Christmas tree. He was an archetypal German. He looked like Bismarck, he laughed like an ogre; he had the air of a man who had founded the German empire himself. A founder, that was it: he had the air of a founder. With a hirsute hand, he put down on my table a package that was the size and thickness of a brick. What monument did he wish to build? What did this first stone signify? I opened it. It was Kafka’s The Castle.” One must bear in mind exactly what that brick looked like: five hundred pages, the cover embossed with the title in gothic lettering, and a title page featuring a photo of the author. Vialatte was unaware, then, that that face would soon represent a destroyed world: that of Germanophone Judaism in central Europe. The portrait showed a man in a tie that was slightly skewiff, the corner of his mouth upturned in a slight smile. Vialatte thought at first that he was looking at Jean Cocteau. He knew nothing of this man, not even the fact that he had died a year earlier, and that a certain Max Brod had undertaken to release his works – left unfinished – one by one. So it was that Vialatte received his translation mandate, one winter’s morning, just as Joseph K., before him, had received his arrest warrant, without being notified of who had ordered it, nor of the reasons.

“Who exactly was Kafka? I always sought to avoid ever knowing him, to make him a mystery to me. Why talk about him? Why take away from him the prestige of being known only as the author of a one-of-a-kind, bizarre, brilliant oeuvre?” Vialatte was of the abstentionist type: all that mattered to him was the work he had in front of him, a thousand miles from Prague, Judaism, paternal domination, engagement, and office life. Vialatte read Kafka without taking his usual habitat into account. He made him see the world. Vialatte brought Kafka all the way out of his little world, to give him access to a certain kind of universality. By releasing him from the weight of his biography, he revealed the humour hidden in his works. Was it this de-isolationism that explains why it was Kafka’s humour, more than anything, that stood out for him?

Vialatte worked on multiple translations of Friedrich Nietzsche and Bertolt Brecht: Germans who, though not light and gay, were capable of being fiercely funny. Vialatte was without doubt the first person, and perhaps the only one, to believe Max Brod when he claimed that Kafka had managed to make his entourage laugh with stories about a bloke who woke up transformed into a cockroach. Valiatte knew that the element of comedy was a vital, inseparable part of what constituted the Kafkaesque.

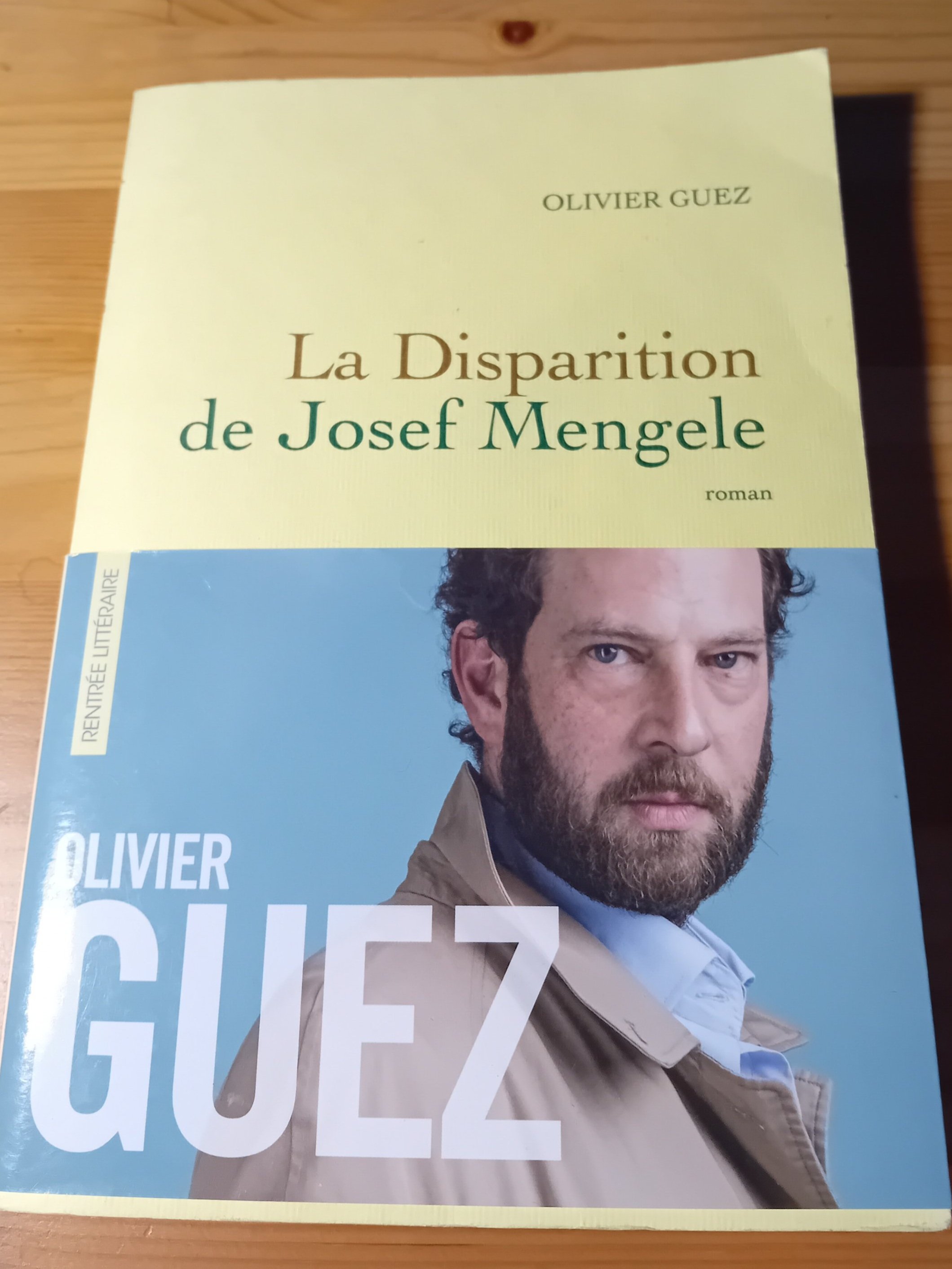

The Disappearance of Josef Mengele

by Olivier Guez

1.

The North King cuts through the muddy water of the river. Its passengers, having climbed up on deck, have been peering at the horizon since the dawn, and now that the cranes of the naval construction sites and the red line of the port’s depots can be glimpsed through the fog, Germans are breaking out into a military ditty, Italians are making the sign of the cross, Jews are praying, and despite the drizzle, couples are kissing, for the liner is approaching Buenos Aires after three weeks at sea. Alone beside the ship’s railings, Helmut Gregor is deep in thought.

He had been hoping that a secret police launch would come and find him, and spare him the hassle of customs. At Genoa, where he had boarded the ship, Gregor had begged Kurt to do him that favour: he had stressed that he was a scientist, a high-flying geneticist, and had offered him money (Gregor had plenty of money), but the people-smuggler had merely grinned and refused to commit to anything: privileges like that were reserved for the top brass, the dignitaries of the old regime, rarely for an SS captain. He would send a cable to Buenos Aires in any case, though – Gregor could count on him.

Kurt had pocketed the Deutschmarks, but the launch had never shown up. So Gregor stands in the enormous hall of the Argentine customs service, with the other new arrivals. He clutches two suitcases tightly in his hands, a big one and a small one, and gazes at exiled Europe all around him, the long lines of anonymous figures, elegant or slovenly, from whom he had kept his distance during the crossing. Gregor had chosen instead to look at the ocean and the stars, or read German poetry in his cabin; he had looked back over the past four years of his life, since the moment he had left Poland when disaster struck in January 1945, and had melted away into the Wehrmacht to escape the Red Army’s clutches: his incarceration for several weeks in an American prisoner of war camp, his release from the camp because he had false papers in the name of Fritz Ullman, his stay at a farm filled with flowers in Bavaria, not far from Günzburg, his native town, where he had cut hay and sorted potatoes for three years while going by the name Fritz Hollmann, then the moment he took off at Easter, two months ago, the crossing of the Dolomites using routes beset by smugglers, his arrival in Italy, in South Tyrol, where he became Helmut Gregor, and then at last his arrival in Genoa, where Kurt the bandit had facilitated the steps he had taken with the Italian authorities and the Argentine immigration services.

2.

In the customs office, the fugitive hands over a travel document from the international Red Cross, a permit to disembark and an entry visa: Helmut Gregor, height 1.74 meters, brownish-green eyes, born 6th August 1911 in Termeno, or Tramin to give it its German name, a town in South Tyrol; German citizenship but Italian nationality, a Catholic, and a mechanic by trade. Address in Buenos Aires: 2460 rue Arenales, district of Florida, c/o Gerard Malbranc.

The customs officer inspects his luggage: the meticulously folded clothes, the portrait of a delicate blonde, some books and a few recordings of opera music, then grimaces on seeing the contents of the small case: hypodermic syringes, exercise books filled with notes and anatomical diagrams, blood samples, microscope slides with cells on them: odd items for a mechanic to have in his bag. He sends for the port doctor.

Gregor shudders. He had taken insane risks to keep hold of this compromising attaché case, the precious fruit of years and years of research, throughout the life he had embarked upon after hastily leaving his Polish posting. Had the Soviets arrested him and found them in his possession, they would have executed him on the spot. As he travelled west, in the great German debacle of the spring of 1945, he had entrusted it to a nurse who had taken pity on him, whom he had later gone to meet in the east of Germany, in the Soviet-controlled zone, an insane expedition, after his release from the American camp and a journey that took three weeks. He had then passed it on to Hans Sedlmeier, his childhood friend and the confidante of his father, an industrial man; Sedlmeier, with whom he had regularly arranged meetings in the woods around the farm where he had laid low for three years. Gregor would not have left Europe without his attaché case: Sedlmeier returned it to him before he left for Italy, an envelope stuffed full of cash inside it, and now here is this idiot with dirty fingernails, about to derail the whole business, Gregor muses, as the port doctor examines the samples and the notes written in cramped, gothic handwriting. Clueless as to their meaning, he questions him in Spanish and German, and the mechanic explains that he is an amateur biologist. The two men fall silent and the doctor, who is ready for his lunch, signals to the customs officer that he can let the man through.

It is 22 June 1949, and Helmut Gregor has reached the sanctuary of Argentina.

17.

Of all his new friends, Uli Rudel is the one Gregor likes best. Shot down thirty-two times, the eagle of the Eastern front always managed to find his way back to the German lines even though Stalin had put a price on his head – a hundred thousand roubles, a fortune. After being hit by an anti-aircraft grenade and having his leg amputated in February 1945, Rudel climbed back into his Stuka two months after his operation and, amid the screech of sirens, destroyed twenty-six Soviet tanks before surrendering to the Allies on 8 May, 1945.

When the fighter pilot shows him the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, with its oak-leaves, golden swords and diamonds, which Hitler handed to him in person – he is the only man to have one – Gregor’s eyes light up like a child’s: Rudel well and truly is a splendid representative of the master race. Despite his prosthetic leg, he plays tennis and has just conquered the Aconcagua, the highest peak in the Americas. He is directly descended from the Teutonic Knights that Beppo used to tell stories about beside the fire lit to mark the summer solstice when he was sixteen and seventeen, when he led the local branch of the Grossdeutsche Jugendbund, a nationalist and conservative youth movement. Rudel is a German warrior, of the kind Gregor imagines himself to be, and as Rudel seems to consider him to be, despite the modest nature of his career. Gregor is just a little SS captain, after all: the colonel enjoys meeting up with him at the ABC club whenever he is passing through Buenos Aires.

Each time they meet, the two Nazis indulge in long conversations. They don’t drink alcohol and think in terms of mathematical categories, sharing the same setbacks in matters of the heart –Rudel’s wife demanded a divorce before he left for Argentina; the same apocalyptic vision of the ‘degenerate’ and ‘amoral’ Weimar Republic of their youth; the same belief that Germany was stabbed in the back in 1918; the same ‘total’ devotion to the German people, to the German blood. It is all about the struggle, everything is a struggle: survival of the fittest, that is the Arian Law of History, the weak and unworthy must be eliminated. Purged and disciplined, Germany is the greatest power in the world.

While dining alongside the heroic pilot, Gregor vaunts his own past as a soldier of the biological war effort, keeping no detail hidden. Mengele lets slip the mask of Gregor. As a doctor, he had tended to the body of the race and protected the fighting corps. He had fought at Auschwitz against disintegration and the enemies within, the homosexuals and ‘asocials’; against the Jews, those bacteria who for millennia had been seeking to bring about the loss of Nordic humanity: they had to be eradicated, by all possible means. He had done what any moral man would do. By putting all his strength in the service of the purity and development of the creative force of the Arian blood, he had fulfilled his duly as an SS officer.

Rudel fascinates Gregor because he has done remarkably well for himself. An advisor to Peron, he is steering the development of South America’s first ever fighter jet, the Pulqui, alongside a brilliant aircraft manufacturer, Kurt Tank, another Nazi exfiltrated from Germany. He is making huge amounts of money as an intermediary between the air-force and several German giants of industry – Daimler-Benz, Siemens, the seaplane constructor Dornier, and thanks to the import licences that Peron generously granted him. With no restrictions on his movements, Rudel travels freely from place to place, back and forth from Europe to South America, at the heart of every intrigue, of all the escape networks for criminals, ODESSA, ‘Die Schleuse’ (the Sluice), ‘Die Spinne’ (The Spider). Rudel, the co-founder along with Von Neurath of the Kameradenwerk, which sends parcels and pays the legal fees of his friends who are imprisoned in the country, is marshalling the Nazi emigration.

Rudel takes Gregor under his wing and at the same time warns him: don’t even think about getting your hands on the Nazi treasure, no-one ever will.

All manner of outlandish rumours are circulating about this famous treasure in Buenos Aires. Shortly before the end of the war, Martin Bormann, Hitler’s secretary and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery, supposedly sent planes and submarines stuffed full of gold, jewels and artworks stolen from the Jews to Argentina: Operation Scorched Earth. Word has it that Rudel was one of the men who brought the treasure over, depositing it in several accounts opened in the name of Eva Duarte. After their marriage, Perón is said to have got his hands on the Nazi gold, enabling his wife to finance her foundation. A short time ago, two bankers suspected of administering the booty were found dead in the streets of Buenos Aires.

“That aside, anything is possible in Argentina,” Rudel says to Gregor. “Do you know my mantra? Only he is lost who gives himself up for lost.”

18.

So Gregor seeks emancipation. With the blessing of his father and Sedlmeier, who continue to send him funds, he will represent the family business in Argentina, prospecting for customers in the enormous markets for agricultural machinery on the sub-continent. Rudel encourages him and takes him by private jet to Paraguay, the idea being for him to find some collaborators: the country shelters colonies of German farmers, the oldest of which, Nueva Germania, was founded by Elisabeth Nietzsche, the sister of the philosopher and a fanatical anti-Semite. The southeast has an abundance of fertile prairies, and the barrows, combine harvesters, and manure and fertilizer spreaders there would be precious to Mengele. The country is safe, too: Rudel has numerous friends there who, in 1927, founded the first ever Nazi party outside of Germany, in Villarrica.

Sassen puts some thought into how best to help his friend the doctor, too. He offers him an occasional money-making scheme, a job which, though more delicate, requires someone of his calibre and is highly paid: helping brazen young bourgeois girls to absolve themselves of their sins discretely in Buenos Aires rather than have to give birth in a far-away city and hand the baby over to an orphanage. Having an abortion is a crime that is very severely punished in Catholic Argentina, but Gregor accepts the contract. Since moving in with Malbranc, he has managed to retrieve his briefcase of samples and medical instruments (scalpels, blades, tweezers). It is an opportunity to be of service to the most respectable families – how could he say no? His hands are restless, they are going to renew their acquaintance with the practising of medicine once again, at last, after all these years working as a warehouseman and a farmer.

As the end of the year 1950 approaches, there is a certain euphoria in the air among the fascists of Buenos Aires. The Third World War seems to be just around the corner, Perón is keeping a close watch on the telexes, one finger on the trigger, and the situation in Korea is escalating. President Truman is promising to use America’s entire military arsenal to counter the North Korean offensive in the South, General MacArthur is laying down a belt of radioactive cobalt between the Yellow Sea and the Sea of Japan to prevent the Chinese and the Soviets from entering the fray.

While waiting for Perón’s dreams of empire to take on a more concrete form, Gregor and his new friends are living it up. With gleaming boots and lacquered hair, Haase and Gregor attend performances of Wagner’s Tristan and Bizet’s Carmen at the Colón, the most beautiful theatre in the world according to Clemenceau. Both music lovers, the architect and the doctor take their post-performance supper at the café Tortoni or at the Castelar, and between mouthfuls of the choicest beef steak, talk of how sublime German music is, of how it embraces all the senses and approaches the infinite. Sassen, who loves Mexican variety shows, occasionally takes his friend, with Fritsch, to the cabarets or to the Fantasio d’Olivos, with its fetish dancing, frequented by actresses and producers. It is a role-playing game: Fritsch foots the bill, Gregor ogles sirens with Indian hair, Sassen drinks, dances, and gropes, yeguas – mares – and potrancas – fillies – while his wife and daughters sit around at home. Twice a week, on Wednesdays and Saturdays, Gregor goes to see a lechera, a fellatio dispenser, in a club with dimmed lighting in Corrientes, another one of Sassen’s suggestions. Gregor forbids these docile girls from touching his skin – just his cock; no kisses, no intimacy; he pays, ejaculates, and leaves.

When it gets too hot in Buenos Aires, they spend their weekends in the pampa, at the home of Dieter Menge, a former pilot, another friend of Rudel’s, who made his fortune by recycling scrap metal and has a large estancia lined with eucalyptus trees and acacias. There is a bust of Hitler to brighten up the garden; a granite swastika adorns the bottom of the swimming pool. At Menge’s place, the evenings are drawn out, the air is transparent and the men are welded together by the profession of firearms, ordeal by fire, the old certainties. The Nazis sit around in shirt-sleeves drinking beer and Schnapps, barbecue quarters of beef, a suckling pig, grilling and talking of the distant fatherland and of the war; Gregor is not particularly garrulous but Sassen excels at this little game, feverishly imitating the crash of grenades and the screaming of projectiles, re-awakening the waves of fire, the memory of the blackened faces and ragged uniforms of Stalin’s Siberian divisions. Every year, on 20 April, Menge and his band organise a torchlit procession to celebrate the Führer’s birthday. Sometimes, Rudel brings a new arrival to the promised land. This was the case with Wilfred von Oven, a former close collaborator of Goebbels, or a prestigious visitor who was passing through, like the former SS officer with the scar, Otto Skorzeny, who, while high on methamphetamines, had whisked Mussolini away in a glider to be kept under house arrest in the Abruzzi after the Allies landed in the south of Italy. Having now reinvented himself as an arms smuggler, Skorzeny claims to have seduced Evita during the Spanish leg of her Rainbow Tour, “bang-bang, she was a damn animal, Señora Peron”, he trumpets: Fritsch chuckles, and Sassen proposes a toast to the Reich and to Argentina, where the Nazis have it so good.

In the middle of March 1951, Menge gets the savage horde together at the estancia. Rudel, Malbranc, Fritsch, Bohne, Sassen, Haase, they all show up to celebrate their pal Gregor’s fortieth birthday. And they bring him a gift. It is one of Dürer’s engravings, a mythical scene: Knight, Death and the Devil.

37.

It is now a race against time. The extradition request for Mengele has been sent by Bonn to Buenos Aires, and a second one is winging its way to Asunción, for word has it that he may have taken refuge in Paraguay. In Argentina, the process is slowed down, mired by countless legal and administrative obstacles, the German ambassador, Junker, digs his heels in, and dithers, the request goes around the houses, from the Foreign Ministry, to the president of the Senate, to the general prosecutor, to a Federal Court judge, the police, the courts. In their hearts, the Argentine and West German governments are happy with this huge imbroglio. In Paraguay, the Home Affairs Minister and the police get wind that an extradition request could be forthcoming, for Interpol has asked them for a copy of the file of the applicant for naturalization, but Rudel intervenes with the Minister. His friend, the brilliant doctor José Mengele, is being pursued because of his political beliefs in Germany, there’s nothing more to it than that, he will be of precious value to Paraguay, so he should be naturalized as a matter of urgency: in November 1959, it comes to pass, Paraguay’s Supreme Court grants Mengele citizenship, a residence permit, a certificate of good behaviour and an identity card.

Yet when Mengele arrives at the Jungs’ house, where a little party is being thrown to celebrate the good news, he looks shattered. His eyes brimming with tears, he manages to mutter the news: his father has just passed away. Germany has lost a patriot, and he has lost his staunchest ally, his shield, that awe-inspiring and intransigent father who never relinquished him, in spite of everything. Thousands of kilometres from Gunzburg, where an imposing portrait of the deceased has been put up on the façade of the town hall, Mengele pours out his rage beside the swimming pool, giving it an earful in the sticky Asunción night. To von Eckstein, Karl-Heinz, the Jungs, the Haases, and Rudel, he tells the story of his ascent of the Hirschberg with his father, in the summer of 1919. For once, it was just the two of them, they had taken a picnic with them, a butterfly had landed on his sleeve and from the summit, the lakes of Bavaria were glistening like rolls of gilded film. Before going to bed, when he was a child, his father, of whom he had been so afraid, would say a prayer in Latin, one he had learnt from some Trappist monks after he nearly drowned in a rainwater tank, at the age of six: procul recedant somnia, et noctium phantasmata: let the dreams and chimeras of the night stay far away from us.

Inconsolable, Mengele mumbles and sobs like a little girl. He will go to the funeral, at all costs, he will take the first flight to Europe tomorrow, Rudel tries to dissuade him, it would be suicide, the police will nab him at the cemetery, he must give up the idea.

On the day of the funeral, the undertakers lay a garland of flowers on the grave, accompanied by an unsigned note: “From afar, I greet you.”

38.

In Buenos Aires, Eichmann, who is now working for Mercedes as a mechanic, may have been located.

Lothar Hermann, a blind German Jew who had fled to Argentina from Nazi Germany before the war, is convinced he is on his tail. For a long time, Hermann’s daughter was seeing a fellow called Nick Eichmann, who used to boast of his father’s exploits during the war and expressed regret that Germany had not annihilated all the Jews. In 1957, Hermann writes to the prosecutor of Hesse, Fritz Bauer. Rather than collaborate with the German intelligence agencies and the German Embassy in Buenos Aires, which are infested with former Nazis, Bauer opts to pass on the information discreetly to Mossad. The Israeli intelligence agencies initiate an enquiry in Argentina but it is not conclusive, and Mossad cuts short its investigation: Hermann is asking for too much money; the alleged address of the man suspected of being the mighty exterminator of Europe’s Jews is a hovel, in the suburbs of Buenos Aires. It is unthinkable. But Bauer is inclined to believe Hermann’s allegations. He tracks down a second source who corroborates the man’s story: Ricardo Klement is indeed Adolf Eichmann. This time, Mossad is going to act on the information; the decision to kidnap the SS is taken in December 1959.

Isser Harel, Mossad’s director, secretly plans to carry out a second kidnapping: he dreams of adding Mengele’s name to those of the other men he has hunted down. The West German extradition request has found its way into the press and the World Jewish Congress is encouraging the survivors of Auschwitz to testify about his hideous crimes to Langbein. Harel’s information is sparse and out-of-date: Mengele is going by the name of Gregor, he is the director of a furniture factory in downtown Buenos Aires. His plan is simple: after Eichmann’s arrest, due to take place on 11 May 1960, his men will have nine days to track down the Nazi doctor and get him on the plane that will be taking Eichmann back with them to Israel.

Since becoming a Paraguayan national and coming into a share of his inheritance, Mengele has been spending his days trying to put any dark thoughts to the back of his mind. He goes water-skiing, discovers the Guayaki tribes with the eccentric von Eckstein, and can once again look to the future with a certain amount of serenity. The tensions between him and Martha seem to be easing, he has recovered his freedom of movement. Early in 1960, whilst the teams from Mossad are preparing for the kidnapping of Eichmann in Buenos Aires, he spends several days at the guesthouse where she is living with Karl-Heinz, in the district of Vicente López. A few weeks later, in April, they meet up again at the Hotel Tirol, a luxurious establishment in the Paraguayan city of Encarnación. The indefatigable Sedlmeier joins them. They discuss finances, means of communication and the prospects for growing their subsidiary in Paraguay. Mengele shows his acolyte the photos of a beautiful property he wants to buy in the Alto Paraná region. He heads back to Krug’s residence feeling reassured, almost joyful, Martha having finally agreed to the idea of following him into exile.

At the start of May, the Attila operation enters its active phase, with the arrival of the Mossad commandos in Buenos Aires. Harel has slipped a coded version of Mengele’s file into his luggage. On the 11th, as planned, Eichmann is taken off the street. In the hideout where they hold him prisoner, the Israeli agents harry him: does he know Mengele? Where is he hiding? What does he look like now? What are his habits in Buenos Aires? Who does he go and see? “Eichmann, where is Mengele?” The Nazi remains stony-faced. Despite their differences, the contempt in which he holds him, he refuses to betray his fellow fugitive: “My honour is called loyalty.” The Israelis persevere, alternate between promises and threats, insist, until at last, Eichmann gives them the address of the guesthouse in Vicente López.

Time is of the essence, the Israelis are a tight-knit group whereas for the Nazis of Buenos Aires, it’s every man for himself. The moment they learned of their father’s disappearance, the Eichmann sons hurried to Sassen’s house to coordinate the search for him. The Jews are behind this, they are sure of it, and they make plans to blow up the Israeli Embassy or kidnap the ambassador by way of reprisal; they spread their net over the city, aided by the fascists of the Tacuara militias and members of the Péron Youth; Sassen is tasked with keeping a lookout at the airport.

Harel dispatches two agents to the guesthouse, a secluded villa surrounded by a fence at the end of a straight road, hard to keep watch over without being noticed straight away. The woman who owns the guesthouse doesn’t know a Mr Gregor, she says, nor a Mr Mengele. A postman proves to be more chatty: there was indeed a Mengele family that lived there, but the family disappeared a few weeks ago, without leaving an address or having their mail forwarded. At the furniture factory, no-one has ever heard of a German by the name of Gregor. The days drag on, the doctor hiding in Paraguay remains impossible to find, but Harel does not give up. Mengele “burns like a fire in his bones”, the director of Mossad even contemplates an assault on the guesthouse, convinced that he’s still holed up there. His men talk him out of it, he could be about to blow the whole operation.

On 20 May 1960, an El Al plane takes off from Buenos Aires headed for Tel Aviv, with Adolf Eichmann on board, sedated and dressed in an air crew uniform. Harel vows to his men that they will have Mengele’s scalp soon. They will form a new special unit responsible for tracking down the Nazis, and the doctor of Auschwitz will be their first target.

[N.B.: an English version of this novel, translated by a different translator, has now been published.]

THE TRAIN FROM TOULOUSE TO PARIS, 10TH JANUARY 1944

The women whose hands were not cuffed scribble letters and fling them, like messages in a bottle, through the tops of the railway car’s windows; the letters flutter along the entire length of the train and end their mad race haphazardly, in the trees, beneath the wheels of a car or in the middle of a road, visible enough for some charitable hand to grab them and help them reach their destination. The letters talk of concern as to where this journey under surveillance might be taking them, send words of love or encouragement, and occasionally provide simple tips on how to stave off the cold of winter. There is a presentiment of this being a one-way journey, the urgency of a call for help that does not state its name.

‘I’m not very good at writing, please help me,’ Shaya, the woman next to Paule and Alfred, begs them.

Like Paule, she is holding her child in her arms.

Her husband is in handcuffs at the other end of the railway car. Originally from the little village of Beguilosson in Poland, Shaya and Zelman fled Nazi rule and found refuge in the Haute-Garonne region, where he worked as a tailor and she as a maid, before the Germans’ occupation of the Free Zone plunged them into precariousness and danger once again.

Paule offers reassurance and sets about writing a few lines intended for the family that were Shaya’s employers. Shaya had been on her own, in Rue Saint-Louis, Toulouse, when two militiamen came looking for her. She knows that the couple, both doctors, have humanity in their hearts. She knows that, if need be, they will find a way to notify her husband’s older brother, who lives further south, near Carcassone. Paule writes his address as clearly and legibly as she possibly can. Alfred, who has been spared the handcuff treatment, looks on in wonderment as his wife, who won him over the very first day they met, does this act of kindness. The mere fact of having found them again – her and their little one, Annie – after the violence of the arrest and separation at Saint Michel prison, is a small victory. Hundreds of people from Toulouse have been put on this train, and Alfred’s face is one that everyone recognizes. Nakache is still a star, despite having been absent from the pool of late. He attracts looks of admiration, sometimes of concerned bewilderment: Why has he been brought along too? Even the French policemen who encounter him treat him with kid gloves.

One young man opts for a bolder approach. His name is Léon. He is twenty-three. He is accompanied by Louise, his older sister, who has remained seated at the front of the railway car. On the day she was arrested, Louise managed, by some instinctive reaction, to save her five-year-old daughter by passing her off as the child of the concierge. She now knows her to be in a safe place.

Léon walks up to the great champion.

‘I’m glad to be able to talk to you. I’ve kept track of all the records you’ve broken in the last couple of years,’ he grins. ‘It drove the Germans up the wall.’

‘What about you, what do you do?’ Alfred says in reply.

‘I was a telephone operator in Toulouse, but I got fired. Since then, I’ve been doing odd jobs as an electrician, here and there. I get by. Prior to that, I was just a poulbot.’

‘A poulbot?’

‘A Montmartre street urchin! That was where I learned to sing. I spend my life singing. Some people pray when times are bad, some people cry, others fall silent. As for me, I sing!’

‘And you’re absolutely right to do so, my man! What about your parents, where are they?’

‘Still in Paris.’

‘Isn’t it too dangerous?’

‘They have a little fabric shop, right opposite the police station in the 18th arrondissement. God only knows why, but the chief of police promised to protect them. My parents trust him, and they’ve never declared that they’re Jewish. Maybe the police chief is impressed by the journey my father has made: a Romanian fighting with the French army in the trenches, a true believer in Socialism, then a naturalized citizen of France, a father of five… And not a penny to his name!’

‘You may well be right,’ Alfred says as the train slows down once again, then comes to a stop.

‘A chance for me to make a run for it,’ Léon mutters under his breath, looking all around him. But Louise, his sister, keeps saying over and over: I can’t run, I can’t run… At Matabiau station, there had been such a mêlée that it might have been possible to slip away unnoticed.

‘Don’t take any undue risks, Léon. And keep an eye on Louise.’

The train snaked along the circuitous route from Toulouse to Paris. It took twenty-four hours to arrive at the Gare d’Austerlitz. On the platform, with the day only just d, a constable leads the detainees towards dozens of requisitioned buses. Where will the buses take them? No-one knows.

The Parisians setting off for work don’t seem to suspect anything untoward; don’t seem in the least bit concerned.

The Swimmer of Auschwitz

by Renaud Leblond

N.B.: As with The Disappearance of Josef Mengele, The Swimmer of Auschwitz has been published in English since I first pitched the book to a publisher (by a different publisher, and translated by a different translator)

Dmitry Bykov’s novel June

I am seeking a publisher for my translation of Dmitry Bykov’s novel June. I was selected as one of the translators in the RusTrans research project organised by Professor Muireann Maguire and Dr Cathy McAteer, academics from the Universities of Exeter and Bristol, respectively, aimed at researching the publication process for contemporary Russian literature in translation. The following info is taken from the RusTrans project’s website:

Huw Davies is planning to translate Dmitrii Bykov’s historical novel June (Июнь, 2017). Despite his notoriety in Russia as a journalist, novelist, essayist, and liberal-minded public intellectual, very few of Bykov’s novels have been translated into English (with the notable exception of Cathy Porter’s version of his ЖД (2006) as Living Souls in 2010 for Alma Books. Bykov’s biography of Boris Pasternak (called simply Boris Pasternak) won him the National Bestseller and Big Book awards in 2006. The novel June has sold over 43,000 copies and claimed third place in Russia’s prestigious Big Book Prize in 2018. Bykov says of June that, although it is not directly about him, it contains more painful truths about him than any of his other works. Critics have called it his best novel to date.

The cover of the Russian edition of Bykov’s novel June

Июнь (‘June’) by Dmitry Bykov

In this excerpt from part one of the novel, Misha Gvirtsman, a student at the Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History in Moscow, faces the threat of expulsion from the Institute, after having been wrongly accused of harassing a female student. A meeting of the student body has been convened so that the complaint brought against Misha can be discussed and acted upon.

Pages 50-59.

Someone had forced her to make the allegation, he rightly surmised – but whose toes had he trodden on, to make them want to do that?

“Comrades,” said Draganov in a high-pitched, scoffing voice, stepping out onto the podium. “I asked you to gather here today so that we could respond as a matter of urgency to a complaint brought by Komsomol member Miss Krapivina, the widow...or rather, the girlfriend of our student Nikolai Tuzeyev, who was killed in battle near Suoyarvi. Miss Krapivina was subjected to harassment of the rudest form on the part of one of our students, one of our comrades” – he paused, just long enough for everyone to wonder, in horror: It wasn’t me, was it?! No, don’t be daft – not guilty even in thought, let alone deed! – “Mikhail Gvirtsman.”

There was a sharp intake of breath around the auditorium – or rather, the release of it, in a collective sigh of relief: no-one imagined Gvirtsman could have done anything violent, and consequently, there was no cause for alarm. Misha started smiling with shame, blushed, and suppressed a desire to take a bow. A fellow called Soifert even winked at him. This might all come to nothing, it really might.

“I am not going to ask Komsomol member Krapivina to share details of the circumstances. Take my word for it, they took place, I have studied the situation. We shall listen to what Comrade Gvirtsman has to say, and he will set it all out to us in person. I propose that we then express our views on the essence of the matter.”

“How can we talk about the essence?” people shouted out from their seats. “We didn’t see anything!”

“Gvirtsman should be given a pat on the back!” someone shouted from their seat in a facetious voice. “He doesn’t pay women enough attention, it’s insulting!”

“I should like to call upon you to take this matter seriously,” Draganov intoned, as if preparing to turn this kangaroo court into a farce at any moment. “Comrade Krapivina feels she has been insulted!”

“Let’s hear Krapivina’s side of the story!” a clamour of voices demanded.

“I don’t know, comrades, whether she would feel comfortable...Are you willing to speak, Comrade Krapivina?” Draganov asked courteously.

“Yes, I am,” Valya said, and she got to her feet. “I’d prefer not to come up to the front though!”

“Of course,” Draganov nodded, “of course.”

“On the third,” said Valya, then she fell silent. “Of this...of the present…year,” she went on, “we were at Klara Nechaev’s place. Everyone had had a bit to drink. No-one was drinking heavily though.”

A murmur of approval rippled around the auditorium once again.

“Always the way, when there isn’t enough alcohol,” the same wit as before shouted out.

“A few individuals were out of control, though, and then Gvirtsman,” Valya said, and then she fell silent again. “While people were dancing…he took the liberty…there have never been any ties between us at all. I haven’t let anyone so much as...as you know. But Gvirtsman, all of a sudden...he didn’t give me any warning about anything.”

“What was he playing at!” a female voice cried out – Sasha Brodskaya, Misha reckoned.

“And then it happened,” Valya muttered, haltingly. “He tried to kiss me, I pulled away. He tried to hug me, I pulled back further. People noticed, it caught their attention. I don’t know what they must have thought of me. I wanted to give him a slap, but I stopped myself. He got the message without that being necessary. And since I think that it’s immoral, I’d like to see him censured. Censured by everyone.”

“She’s an outright deviationist if you ask me,” Poletaev whispered to Misha, leaning back over his chair.

“Well comrades, you have now heard the whole story and you may express your views,” Draganov suggested.

After raising her hand like a schoolgirl and not waiting to be given permission, Golubeva stood up, all red in the face and jerky in her movements, a slightly putrid smell forever issuing from her mouth. Misha was convinced she was about to speak out in his defence, and he felt ashamed at having recalled her bad breath.

“I can hear people sniggering right now,” Golubeva started saying, scarcely able to hold back her sobs. “And yet, comrades, I don’t know what there is to laugh about. It stems from the patriarchal way of life, this disrespect for women, and all this talk about how if a woman says ‘no’, she really means ‘yes’. Regrettably, I see these phenomena here among us, too. Here, where we ought, one would think, to be experiencing a new way of life, in the twenty-third year of the revolution, we are witnessing the most unbridled shamelessness. It’s not even a petty bourgeois phenomenon, it’s lumpenism, comrades. And the idea that a so-called poet should take the liberty of…I for one never saw that coming. But if you think about it, comrades, I did see it coming. I ought to have seen it coming, because I keep seeing manifestations of this sort of thing. I know that a lot of girls are simply too ashamed to make allegations. But as I see it, there is nothing to be ashamed of!”

“Down with shame!” the self-appointed jester called out – but no-one laughed: things had taken a serious turn.

“Allow me,” said Kruglov, a serious young man, and aptly named since he did indeed have round cheeks[1], and looked like Delvig – apathetic, but capable of sudden brusqueness. “The way I see it, comrades,” he said, running his hand through his hair, “we have somewhat, er, strayed into a sphere that is not ours to explore. One can go back as far as Engels, who warned against putting people’s private lives up to scrutiny.”

“Where did he say that?” someone asked from their seat. Misha suspected that Engels had not made any such warning and that such an idea had never even occurred to him – he couldn’t possibly have imagined an event like this twenty-three years into the dictatorship of the proletariat – but Kruglov could cite most of the useful quotations, and if really pressed, he would have been able to invent the requisite passage.

“In The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State,” Kruglov declared, rapping out every syllable. “He directly states that matters from people’s private lives should not be examined at public gatherings. Morality is not something that is formulated based on a majority share of the vote. I was not, so to speak, present at the time, I was not in the room, so to speak. It seems to me that comrade Krapivina would have been well-advised to have discussed the situation with Gvirtsman in person, perhaps even given him the slap that she so pusillanimously refrained from giving him, and then we wouldn’t need to be wasting time today denouncing a kiss – a kiss that, as far as one can tell, didn’t even take place anyway.”

Kruglov was a popular fellow, and a few of the students even applauded his contribution. You could see from the look on his face that he could get away with being like that, that he had been given permission; one can always tell when someone feels they have permission to do as they please, even if that permission was given to them by no-one but themselves. And after that, the whole thing might have fizzled out, because that was the outcome Draganov himself wanted – Misha could tell. He was already getting ready to summarize the proceedings, give him a reprimand, call on everyone to redouble their efforts to behave appropriately, and so on and so forth. But at that moment Nikitin stood up, and set in motion a chain of events which, even now, Misha could not recall without feeling a sense of revulsion.

He could never have expected such a thing of Nikitin (he was no Golubeva, after all). Nikitin was a twitchy, anaemic, spineless fellow, with clammy hands and a nervous tick. Everyone disliked him, but they did so the way people dislike a significant phenomenon, one that leaves you with no choice but to put up with it. He was writing something, a work that was eternally unfinished, but, it was rumoured, remarkable. He had read Joyce. Misha had once read a bit of Joyce in an edition of International Literature and understood that it was art for the top ten thousand, and, in the grand scheme of things – of no real use to anyone. Nikitin was always coming out with stupid utterances, but making them sound deep and meaningful. Misha’s attitude towards him was one of forbearance. Nikitin was sort of a prime candidate to fail in every subject, the most vulnerable and pitiful of all the students on campus, but that pity was the very thing that protected him better than any special patronage would have done. It was as if everyone was afraid of crushing him completely. And so it was inconceivable that a blow should be struck by Nikitin – who was he to talk?! – although Misha immediately saw the flawless logic of it: Nikitin had to deflect attention away from himself and, at any cost, make someone else the odd one out.

And so, adjusting his spectacles incessantly with his sticky thumb and forefinger, he began by saying that “it is all well and good to have a laugh, but the reason for doing so, in this case, is no laughing matter. I shall not go into the women’s issue now, private matters, all that malarkey. But there is a category of people among us who are always sneering. I have personally heard our comrade Gvirtsman, I have heard him on several occasions, making fun of students who are, probably, less well-informed. What can one expect, Gvirtsman has lived in Moscow, he’s the son of a doctor, I believe, he had the opportunity to study at an excellent school. But the point of our institution is to teach those who are less knowledgeable and have not had such good schooling, and when has Gvirtsman ever educated anyone? To whom has he offered help? I have only heard him, among a crowd of other equally condescending alumni of Moscow schools, making fun of provincials, including comrade Tuzeyev, who is no longer with us. And it may be,” at this point Nikitin glanced up and looked straight at Misha, and it was the look of a triumphant cobra just before it launches itself at its prey – “it may be that comrade Tuzeyev’s verse was indeed slightly less than perfect. Not like that of Gvirtsman, for instance, who has mastered the technical aspects of poetry. He has mastered them, let us admit that. Let’s give him his due. But he has nothing to say, for he has seen nothing of life and has no wish to do so. And when Tuzeyev, whose verse, I repeat, was, sure, less than perfect, stepped forward and signed up as a volunteer – there was more poetry in that one act alone than in all the slick and highly literary works of Gvirtsman and his supporters.” (What supporters, thought Misha, what on earth is this drivel? Is he referring to Boris?!) “Why was it, after all, that Gvirtsman allowed himself to commit such a brazenly boorish – if we’re frank about it – act? The only reason he did so was that he genuinely does consider himself to be on a higher plane – above the law, the collective, Tuzeyev, Krapivina… And that mockery, that separateness, that narrow circle – how can all that be tolerated? Why is it that someone, on the basis of being personally fortuitous, as a birth-right, I would dare say, can, in this country…”

And on and on it went.

For a while, Misha listened and tried to make sense of what he heard, but after a while he understood only that there was a general desire to drown him, and that a quiet dislike of him that went way, way back, and that he had always sensed, had finally come crawling to the surface; hadn’t there been times when he had felt people eyeing him with hostility, and whispers being exchanged, as clammy as Nikitin’s fingers. And he could not understand why he had to put up with all that, but now he suddenly got it. The Queen of Spades stands for the resentment that we secretly harbour against others. That was what that whole, strange tale had been about – a story that was so un-Pushkinlike, really, one that had come out of nowhere. It had always seemed to him to be no more than a bagatelle, but Pushkin had felt a secret resentment being harboured against him his entire life. Everyone looked on him disapprovingly, in the expectation that, one day, this golden boy, this idle roisterer, would eventually implode. That was what Valya Krapivina had accomplished: she had dragged all this up to the surface. For all it mattered, Misha might just as well not have kissed her – or indeed done anything at all; they would merely have seized upon the way he tied his shoelaces, and claimed there was something untoward about it.

“That,” Nikitin concluded, “that is what I wanted to say, and it is no joke.”

And it was then that Goltsov came crawling out.

Oh, Goltsov. The funniest part was that for a moment, Misha felt a little surge of hope. The thought occurred to him that it was clammy, faded, unstable types that had problems such as a secret resentment of others, and that Goltsov was different, straightforward and strong, and he would come to his defence. He would say what needed to be said. And Misha attempted to smile at him, but, fortunately as it turned out, Goltsov was looking the other way.

He started speaking in his customary manner straight away, nipping all hope in the bud. Needless to say, there was nothing humane in what he said. The novelty lay in the fact that he and Nikitin were acting in tandem. They had probably plotted this in advance, and the result really was an effective one-two combination: one of them laid down the theoretical groundwork, the other delivered the blow with proletarian fury. The only thing that made no sense was how Misha, of all people, had managed to rub them up the wrong way: he had never gone anywhere near Nikitin, and had barely even noticed Goltsov. Apparently, though, they had somehow sensed that the less there was of Misha around the faculty, the more there would be of them. Goltsov simply swung his axe, proletarian style.

“I, comrades, am not going to enter into all that petty whiffle, from the classics and all that,” and he nodded in the direction of Kruglov.

Goltsov had clearly had the cheek to rehearse this in advance and construct the required image: this sort of thing could not have just come into being by itself, without artifice! Even the most natural-looking horticultural object is the culmination of the gardener’s efforts, over many years, to cultivate it.

“I am not going to dissect the arguments and identify all the right ones, but I will say this. Nikitin is spot on. He is spot on, comrades, in that what we are dealing with here is a straight-up insult. And it is not Krapivina that has been insulted, comrades, it is us. And I sensed there was something rotten right from the start, because Gvirtsman is not part of the collective, and because, when the volunteers set off for the war, he was doing his thing, sniggering in the corner, back then too! Even now, look at him, he can’t look you in the eye. Right now, he can’t look the collective in the eye and he can’t say anything! Because he doesn’t even know how to speak, all he does is equivocate and sneer, and it’s the same in his poems. Now I may not be an overly sophisticated fellow” – at this point he went into a sort of trance, and Misha could distinctly feel the pleasure, a pleasure not far short of ecstasy, with which Goltsov was working himself up – “I’m of the simple sort, like Krapivina over there, and, comrades, I feel her pain. But it is high time we got rid of this lordly attitude, you know, this scornful condescension! It has only just come up to the surface, but it has always been there. And I will even go so far as to say, albeit some may take offence, comrades, there’s no harm in that – I will say that the more there is of this cultural sophistication, all this high-brow sparkle, at the top, the more common-as-muck, brutish boorishness there is lower down, comrades! Boorishness of the very worst kind, plain and simple. And I propose that we purge the ranks once and for all, because it is an oversight on our part, we need to admit to ourselves that we are guilty of an oversight. Yes.”

Goltsov would have gone on talking for a lot longer, but at that point Misha sensed that the situation had changed drastically, that he really was doomed and that he had only himself to blame. He had tolerated what was happening for too long and had raised no objections. And when Goltsov got back onto the subject of his glossy veneer and lordliness for a third time, Misha leapt from his seat like a coiled spring, and started shouting: “Comrades, what the hell is all this?! Are you listening to this nonsense he’s spouting?”

Pages 207 – 211.

Misha’s blood ran cold: it was to be the worst-case scenario, then; but he got a grip on himself, for he was a fallen angel now and he could not expect life to be plain sailing. And it was good that it was happening straight away, like this. One sensed one was dealing with an organisation that was not messing about.

“I’ll be reinstated at the university,” he said suddenly, in a quiet little voice; what a rotten bit of villainy this was!

“Of course you will!” the lieutenant said in a warm, amicable tone. He couldn’t be much older than Misha, in fact the two of them might well be the same age. Misha had now been swallowed whole and almost digested; it was okay to be a little more friendly towards him. “You’ll serve your time and then go back to university. You’ll be a whole new man. Now get on over to the medical commission, forward arsch.”

Misha and the other naked conscripts – they looked a little younger than him, as if they had come straight from school – underwent a medical examination. He had a heart murmur, of course, and he declared as much straight away, along with the consequences of numerous sore throats as a child, and the physician nodded sympathetically. Given the circumstances we find ourselves in, though – well, you don’t need me to tell you…

Misha was to be conscripted immediately; they had for some reason told him the number of the directive that said so, but he was blowed if he could remember it. Without knowing why, Misha found himself thinking that this was all down to her, down to Valya. If she hadn’t pierced my protective bubble so horrifically, I might still be flying under the radar today. But there had been a flashpoint between us, our own Northern Lights, a magnetic disturbance, and I discovered myself. And but for that, no-one would have spotted me, and no-one would have drafted me into the army, and I would have carried on working as a nurse for as long as I wanted, right through until the summer, then until the autumn, then until my student days are over…

He was handed a health certificate stating that he was ‘Fit for service’ and, after two hours of being shuttled around from office to office in the altogether, he was brought before the lieutenant’s desk again.

“Put your clothes back on and you’re good to go,” the lieutenant said. “You will resign from your job and come back here tomorrow. And say your goodbyes, and all that. But don’t overdo it on the drinking front, if you want my advice. You’ll have a headache and all that afterwards. Forward arsch.”

He was terribly pleased with life. There was some sort of merriment emanating from him, a degree of contentment only normally seen in pigs.

Misha left the military commissariat. Snow was falling gently, and he fluttered around exactly like a little schoolboy, and everything was so quaint, it really was, just like in childhood, when all the decisions are taken for you; like anyone who has been dealt a crushing blow to the head, Misha felt a slight sense of satisfaction, of serenity, of being temporarily resigned to his fate. And sitting there just as quaintly, amid this quaint snow, on the bench outside the military commissariat, was Nikitin, his hands shoved in his pockets. He had for some reason been waiting for Misha to emerge.

“Gvirtsman, hello there,” he said, and he stood up, looking as though he were about to make a speech, but then suddenly at a loss as to what to say. “I have been waiting for you, Gvirtsman,” he suddenly uttered, although that was the last thing that needed articulating, given how blindingly obvious it was. The formal tone with which he spoke was odd, too. The two of them had never exchanged a word in their lives, yet here he was being all formal – what unnecessary etiquette.

“So I see,” Misha said brusquely.

“Gvirtsman, I expect you hate me, but that’s a mistake on your part,” Nikitin said in a dull voice.

“I don’t really remember you all that well, to be honest,” Misha said, telling a barefaced lie.

“Well that’s regrettable, you would do better to remember me. Let’s go for a stroll.”

“Why does it behove me to take a stroll anywhere with you?”

Try as he might, Misha could not strike the right tone, for if he revealed too much enmity towards Nikitin, it would mean that he did in fact remember him, and the attitude Misha was going for was one of boundless indifference.

“It doesn’t behove you to do anything, but we would be better off going for a walk,” Nikitin said, almost merrily. Let’s go and get some tea, I’m freezing.”

And they set off, like two best friends, towards a nearby bakery. This whole absurd episode, from the draft notice in the thick of winter to the sudden appearance of Nikitin, who, evidently, simply lived in the area and was registered at the same military commissariat, was dragging on and taking on a whole new breadth, and by now, there was nothing remarkable about the fact that Misha was walking along next to his enemy, on his way to partake of some tea and bread rolls with him.

“This is on me,” Nikitin said hurriedly, as if to make the miracle complete.

Misha shrugged his shoulders.

“Gvirtsman, I ought really to have met up with you some time ago,” Nikitin started saying, after a short pause during which they both took bites out of their freshly-baked rolls, helped down with gulps of hot, if rather tepid, tea. Everything about the bakery was as insipid as Nikitin, in fact, and the tables had that same sticky quality that he had about him, too. “I ought to have explained things to you, but I hoped you would understand.”

“I don’t need any explanations from you,” said Misha. “They won’t lend any beauty to your actions, so don’t bother.”

“That’s as maybe, but it’s not for the sake of beauty that I wanted to talk to you.” Niktin smiled, looking unaccountably smug. “It’s not my beauty that interests me, but yours.”

And he burst out laughing, his laughter sounding somehow deranged.

“It occurred to me that it wouldn’t be right for someone like you, a man of talent, to stay on at that university. A gifted man, I would even say,” Nikitin added, sipping his tea. “And a real chucky egg,” he added inexplicably, taking another sip of tea.

“But it’s right that you should stay on there?” Misha shot back at once.

“Why talk about me, I’m a finished man, as someone once said. I need to be somewhere, and I’m where chance has put me. You, however, can still be someone, and I decided that there was no sense in you hanging around there, on a palliative.”

“And what makes you think you’ve the right to decide anything on my behalf?” Misha asked, very calmly, without raising his voice. Even as he asked the question, he was thinking about how satisfying it would be to throw a bucket of boiling water all over Nikitin’s ugly mug.

“Nothing, but a man has to take a decision sometimes. Now, I can’t create situations like that myself, I’m a sick man, and my capabilities are limited. If a situation comes about on its own, though, like the one Krapivina set up for you – you can’t think, surely, that I ought to have let you off the hook, to go on living that life, as it were? I am an artist of life, Gvirtsman, that’s the next stage of being a man of letters. One can’t have literature as one’s thing nowadays anyway – so I’m an artist of life. It’s the only genre that isn’t prohibited in this country. If you want to denounce me – go ahead. I can speak openly about it, there’ll be no unpleasant consequences for me. Do you know what you’re going to say next? That, unlike me, you aren’t an informer. And all I can say is: you’re really missing out. It’s a wonderful new genre, a very under-developed one in Russian literature. Chekhov said: write everything you can, except for poetry and denunciations. But I don’t mind telling you, it’s plainly a distinct genre, and it has a future. When there are no normal genres left, the ones on the fringes will flourish. Had you written a denunciation of me, now that might have been literature. Rather than all that doggerel.”

Pages 230 – 232

His mother put all the warm clothing that was to hand, including the quilted trousers his father wore when he went fishing, into a rucksack – and, try as Misha might to convince her that it would all be taken off him anyway, kept holding it out to him without a word, so that, to save her from having to stand there holding such a heavy weight, he had no choice but to take it. Walking with the rucksack on might be easier, anyway, he reasoned. It would teach him some discipline.

Misha walked briskly to the military commissariat, as if he were hurrying to a party rather than signing up for service. He was expecting to see a crowd of people just like him, but there were just five people sitting outside the lieutenant’s office, all of them complete greenhorns, schoolboys who had come to be registered. Misha knocked and went in without waiting in line. The lieutenant looked up from his desk, his eyes pale.

“What brings you ’ere then, Gvirtsman?” he asked.

“My call-up, you told me to come today, didn’t you?”

This was probably some sort of initiation, he reckoned: making it look as though they were not at all pleased to see him, so that he wouldn’t get any ideas about the Motherland being in dire need of his services.

“Forward, arsch,” the lieutenant said. “It’s been cancelled.”

“In what sense?” Misha said, confused.

“In the sense that your call-up is cancelled, you can stand down until the special call-up comes.”

“And when will that be?” asked Misha, scarcely believing his good fortune and wanting to arrive at some certainty straight away. He already knew that in any dealings with the state, one had to get right to the bottom of things, until one had complete clarity, for if any areas of vagueness were left unexamined, they would inevitably work against him.

“Whenever it is deemed necessary. But for now, you’re free to go. You must come back as soon as you’re summoned. Forward, arsch!”

And Misha, still unable to comprehend what was happening, and with his stupid rucksack on his back, walked out onto the porch.

And he promptly broke down, for no reason whatsoever. A veritable torrent of tears came pouring down his cheeks. No explanation could be given for this, other than perhaps one, the most shameful one of all: he had suddenly been pardoned, and a burden of which he had not even been aware had fallen from his shoulders. Had it not been for the rucksack, for which he now felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude towards his mother – cause enough to weep on its own – he would quite simply have defied gravity and floated away, good god! He would have flown into the sky, a sky that was by now almost vernal. And he felt ashamed, and wondered: had I really been that afraid, had this cancelled call-up into an army not currently engaged in any fighting at all really brought him to tears – childish, girlie, shameful tears? And yet he couldn’t recall anything sweeter than these tears in his entire life, because he had had returned to him something that had already been taken away, and he did not know what name he ought to give that ‘thing’: freedom? This occasion needed to be celebrated somehow, the news needed to be shared at once, and he set off at once, almost at a run, to Kolychev’s place, but then remembered that he ought to let his parents know about this miracle he’d been given – Misha never found out what it was all about, by whose sudden whim his February call-up had been announced and then immediately revoked, and whether it had been the same story at all the military commissariats or whether he alone had got lucky.

Where could he call them from? He noticed a chemist’s and fairly flew inside and up to the woman at the counter, asking: “Can I use your phone?” and was given very short shrift; only then did the intoxicating sense of bliss start to diminish. He realised that life was carrying on as normal, that its familiar templates still applied, that he had not arrived at Polycrates’ permanent state of happiness – for had the pharmacist on Kirovskaya Street beamed at him from ear to ear and said: “Be my guest!” it would have meant that he had far exceeded his quota of mercy, and that he would therefore have to pay a terrible price, a price beyond all measure. He nodded gratefully at the woman and ran home.

Pages 245 – 247.

Could he be cured of it? No, there was no cure for it, as far as he knew, and in any case, the people at the clinic would immediately inform his employers. Even if he were to recover from it, the stain on his reputation would last a lifetime. There was a monstrous injustice about the fact that the first woman he had ever been with had infected him with the most terrifying disease known to man. And all because he had failed to recognise that she would be the death of him: after all, she had already ruined his life twice before – and now it was ‘third time lucky’! She might, of course, have infected him that previous time, at New Year’s, but for some reason he felt sure it had happened that time on the stairs. The incubation period could be fairly long, though. There was no-one else from whom he could have caught it, the only other explanation was that it had been passed on from some other resident of his apartment building, but for that to have happened he would have needed to use someone else’s towel, and who on earth would have lent him their towel – the Balandins?! Fat chance. He knew one thing for sure now: he would make her name known to the whole world, even if it meant he would meet his own demise as a result. Before leaping into action, however, and taking revenge on her for everything she had done, he decided to ask her one last question.

He set off for Valya’s place. He remembered the date clearly afterwards – the sixteenth of March.